Docker in vSphere : Part 2 - Install and configure vDVS (to come)

Overview

I am starting a series of articles about running containers on PhotonOS in a vSphere environment with VMware’s implementation of the docker storage driver called “vSphere Docker Volume Service” or vDVS. As a newbie in the world of containers and coming from vSphere, I had a hard time wrapping my head around vDVS and how it works with ESXi and Photon so here’s my shot at explaining it. I will try and give as much information as possible with step by steps for installation and configuration.

In this first post we are going over a few basic container concepts and a quick overview of vDVS.

PhotonOS is VMware’s own stripped down linux distribution with docker embedded, I’m using it as VMware are putting a lot of resources in this product which I think will lead to more and more integration with the VMware ecosystem in the next few months/years. Heck, the vCenter appliance in version 6.5 already runs on PhotonOS! However, everything you’ll read in these posts about docker also applies to other distros like ubuntu, debian etc as the concepts are the same.

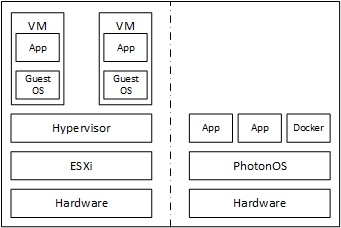

I am not going to get into the “container vs VM” topic as I am sure you have already seen this picture a million times and know what a container is. As opposed to virtual machines, containers share the platform’s underlying OS and only run an instance of a service as opposed to a full blown virtualized OS in a VM. Containers are like Lemmings that can be shot in the head shamelessly, another one will automatically pop up.

It’s simplified but it’s basically it, so let’s move on.

Basic storage concepts for containers

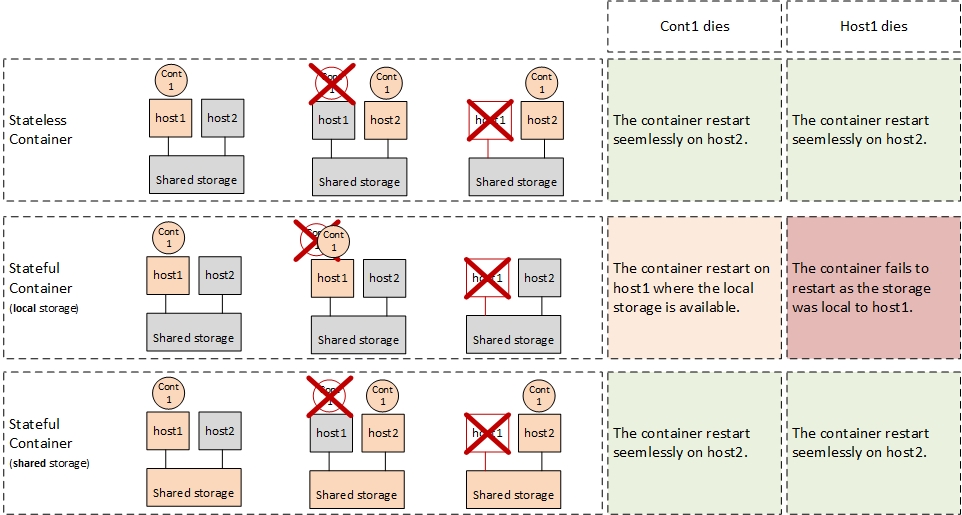

Because this series of articles focuses on storage persistence, we are going to define 2 main food groups of containers:

- Stateless containers: No persistent data here, this is the default behavior of a container. the data is wiped out after reboot/recreation and it doesn’t matter. Example: Web servers.

- Stateful containers: The data MUST persist and must be consistent after reboot/recreation of the container. The persistent volume can be stored locally on the host or on shared storage (recommended). Example: Database server.

Note that the stateful containers are not easily scalable like stateless servers, it must be implemented within the app running inside it (just like setting redundancy for DB VMs is not as straightforward as for web nodes).

The badly drawn exhibit below pictures the loss of a container and the loss of a host with the different types introduced above.

- Stateless: pretty straightforward from a storage point of view. If the container or the host dies it can restart wherever in the swarm.

- Stateful on local storage: If the container dies it can restart on the same host only. If the host itseld dies, the container can’t restart somewhere else because its storage is down as well. The service remains down until the host is brought back online or another accessible volume is assigned to the container (Of course the previously used data won’t be available, it would have to be recovered with some backup mechanism).

- Stateful on shared storage: If the container or the host goes down, the container will be able to restart somewhere else in the swarm that has access to the shared storage.

Of course if the shared storage goes down, your containers won’t have access to their persistent storage. If this happens you most likely have a bigger “sweating issue”…

You probably gathered by now that we are going to focus on the third option (stateful with shared storage) as this is the most relevant one in enterprise scenarios where SLA matters the most.

vDVS in a nutshell

When creating a docker volume, it is possible to specify a storage driver for this volume. The storage driver, like its name suggests, allows docker to leverage different types of storage that are not natively supported to store volumes. Some example of storage drivers:

- HPE 3PAR, StoreVirtual

- Dell SC series

- CEPH

- vSphere Docker Volume Service of course

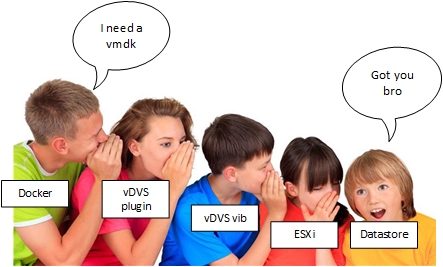

The vDVS driver is made of a vib to install on the ESXi host and a plugin to add to the docker host. I will go more into details in the next post.

The vDVS plugin and the vDVS driver allow Docker to talk directly to ESXi, which in turn manages the datastores and create a vmdk per docker volume on VMFS, NFS, VVol or VSAN. Some kind of chinese whispers 2.0!

You can find the full doc on vDVS here.

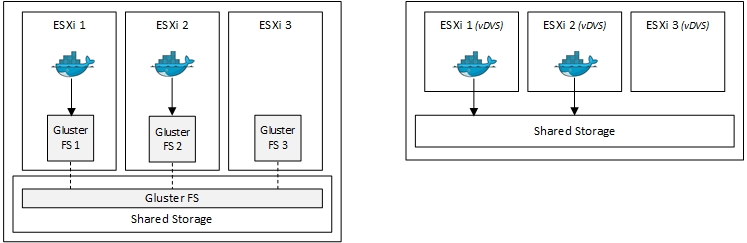

This driver is pretty great as you can store your Docker volumes as regular virtual disks and not have to manage an extra layer of stretched storage like GlusterFS. See picture below.

Host terminology

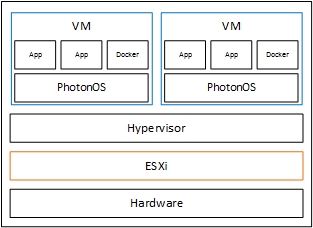

Here I want to avoid any future confusions when I talk about “hosts”. Remember the picture you’ve seen a million times? When you run a traditional ESXi server with VMs on it it is called a host. However when you run say Debian (Photon in our case) with Docker, the Debian server is also usually called a host.

The Docker host can be bare metal (Linux installed directly on the physical server) or virtual (running in a VM). In this series of posts we are going to run Docker in virtual machines so it can get a bit confusing what host is what (see below).

Remember these two for the rest of the visit.

- Docker Host (blue): Virtual machine running photon OS with Docker.

- Virtual Host (yellow): ESXi running on physical hardware.

You might be wondering by now “But why not just get rid of the hypervisor and run the container engine bare metal?”

Well, all services can’t run as containers, or at least not by snapping your fingers. In most cases virtual machines and containers will have to coexist for a time. Though if your structure plans on investing large enough amounts of resources in Docker it might be worth investing in a separate physical environment where Docker runs bare-metal. Another case of “it depends” but I like the flexibility that vDVS and Photon offer.

Docker in vSphere : Part 2 - Install and configure vDVS (to come)